I’ve had an interest in astronomy since I was a kid. In ’88 my uncle gave me my first “telescope” (a small 40mm refractor called Halleyscope – although it was a decidedly unsuitable instrument to watch a comet) and I finally managed to get a “real” telescope in 1991. Telescopes were expensive back then. In Europe they we even more expensive. Fortunately, the dissolution of the Soviet Union opened the borders and we got access to some pretty good Soviet technology carried over by immigrants. So I managed to get a 4.3″ Soviet Newtonian telescope called “Mizar” in Greece at probably much better price than something comparable in the US. Still, at around $250 or so back then it was not “cheap” (I guess around $400 in 2015-equivalent currency). That telescope, solidly built on a heavy equatorial mount is still being exported as the TAL-1 and has a good reputation for its optics. But, man, was it heavy!

I’ve had an interest in astronomy since I was a kid. In ’88 my uncle gave me my first “telescope” (a small 40mm refractor called Halleyscope – although it was a decidedly unsuitable instrument to watch a comet) and I finally managed to get a “real” telescope in 1991. Telescopes were expensive back then. In Europe they we even more expensive. Fortunately, the dissolution of the Soviet Union opened the borders and we got access to some pretty good Soviet technology carried over by immigrants. So I managed to get a 4.3″ Soviet Newtonian telescope called “Mizar” in Greece at probably much better price than something comparable in the US. Still, at around $250 or so back then it was not “cheap” (I guess around $400 in 2015-equivalent currency). That telescope, solidly built on a heavy equatorial mount is still being exported as the TAL-1 and has a good reputation for its optics. But, man, was it heavy!

I was lucky enough to have my sister returning from her studies in the US at that time, bringing along an IBM PS/2 computer and a Canon EOS Rebel film camera. The PS/2 is irrelevant to this article – there was not much an amateur could do regarding astrophotography with a computer back then, but the camera was very useful. You could not hope to achieve much using the cheap point and shoot film cameras of the era, but a serious camera with manual settings did stand a chance. Still, it was a very frustrating experience: You had to get a 24 or 36-exposure roll of decent (and fast) film, so any cheap roll would not do. Popular at the time, if I remember correctly, were the Fuji Super G 400/800, the cooler Kodak Ektar 1000 and for special requirements the Konica SRG 3200. Cost of the roll and the development meant you had to fill that film wisely if you were on a budget. Most importantly, you had to fight with the developer to understand your unusual demands. You see, most astro-images tended not to look like pictures to the developers. They would return the film to you “there’s nothing there”, or cut out the astrophotos. So, you had to insist they develop everything despite the fact that they looked blank, and when printing not try to increase the brightness too much to “show something”. Also you could not shoot many astro-images one after the other, because the developer would not be able to see where to “cut” the film in segments (as my local developers would do). Most importantly, you had no idea whether your method/settings etc actually produced anything, until you finished your roll of film and had it developed. Oh, and did I mention how hard focusing was? No live-view or test-shots!

In all, lunar photos via eyepiece projection were not hard. And even though I did not have access to something like a mylar solar filter, stopping-down the aperture during sunset allowed some solar imaging:

The moon shot with a Canon EOS Rebel held in front of the eyepiece of a TAL-1 reflector. Shot in 1992 on Kodak Ektar 1000.

The moon shot with a Canon EOS Rebel held in front of the eyepiece of a TAL-1 reflector. Shot in 1992 on Kodak Ektar 1000.

Partial eclipse of October 12, 1996. Cloudy skies in Athens, as can be seen on this image projected on a sheet of paper.

Solar eclipse – August 11th 1999 (14:44 as you can see on my Casio Cosmo Phase watch). The eclipse is nearing maximum for Athens. Projected from my TAL-1 reflector.

Solar eclipse – August 11th 1999, the maximum from Athens. Projected on a sheet of paper from my TAL-1 reflector.

Solar eclipse – August 11th 1999 from Athens. Some sunspots visible. Projected on a sheet of paper from my TAL-1 reflector. Blue-2 filter used.

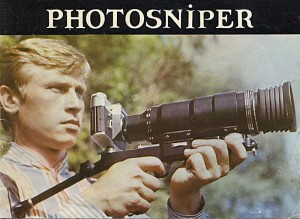

However, harder targets like planets and deep space needed more work, although they were not impossible. The TAL-1 had no tracking but it came with a piggyback mount and a simple cross-hair reticle accessory for the eyepieces. It was not illuminated of course, however I could install it on a high-magnification eyepiece, target a star, slightly de-focus so that the dark cross-hair is visible over the airy disk and diffraction rings and use the manual slow motion controls to track the star, while starting the exposure on the camera. I already mentioned how hard focusing was, there was also trouble if you did not have essentials like a cable release (which was an expensive accessory for the Canon EOS at the time), which meant you had to touch the camera shutter (or actually remove the lens cover as I did) possibly adding some vibration. Soviet technology again helped me in these endeavors. For around $60-$70 I had purchased the “Photosniper”, which was a manual Zenit SLR camera with an amazing 300mm f/4.5 telephoto lens (mounted on a sniper-like contraption). This lens holds its own even against modern expensive lenses, so it is no wonder I managed to get some good images:

Comet Hale-Bopp on April 26th 1997. Zenit 122 with Tair-3s (300mm f/4.5). It is a 2min manually tracked exposure (piggyback on TAL-1) on Fuji Super G 800 plus film.

Comet Hale-Bopp on March 30th 1997. Canon EOS Rebel attached on Helleyscope (400mm f/10). It is a 10min 20s manually tracked exposure (piggyback on TAL-1) on Fuji Super G 800 plus film.

Orion’s sword, including M45 (Orion nebula). An example of both imprecise focus and vibration. Tair 3s 300mm f/4.5, 4min manually tracked piggyback exposure on Fuji Super G 800.

So, coming back into astronomy I was astounded to see that for the same $400 you can now get a decent telescope with tracking (or even goto) and that with a $10 webcam and the proper software you can get amazing photos of planets that were not within reach of amateurs in the past. DSLRs on the other hand have made deep-space imaging very accessible.